THIS WEEK IN

SAG HARBOR HISTORY

(The entries run from latest to earliest, so you may want to start at the very bottom)

Mid-August, 1880 - Fake News.

Counterfeit money has a long history in America. Every few years it seems there was somebody somewhere trying to pass off fake bills or coins. Sometimes, it got bad – very bad: It has been estimated that shortly after the Civil War, one-third to one-half of the nation's currency was counterfeit, posing a major threat to the country’s economy and financial system.

Newspapers did their best to alert the general public when fake bills or coins began to be spotted in an area. The Sag Harbor Express ran just such a warning in May 1880 when it noted that counterfeit silver half dollars dated 1857, 1875 and 1877 were all making the rounds.

So, when just a few months later (Mid-August 1880) large numbers of silver half-dollars dated 1836 suddenly began to appear in circulation, it seemed it was going to be a case of “déjà vu all over again.” However, suspicion and wariness soon turned to excitement and curiosity because, against all odds - these coins were real.

As bright and shiny as when they were first issued – literally in “mint condition” - they defied all reason and explanation as to why they suddenly came to appear. Scores (perhaps even hundreds?) began popping up all over Southampton Town.

What in the world was going on?

News of the mysterious coins – and the explanation behind their sudden appearance - was found so interesting that the news item was picked up and published in newspapers all over the country, as far away as Utah and California.

It seems an old Sag Harbor resident, “well known as a practicing physician, who for years past led a comparatively secluded life,” had, back during the financial panic of 1836, hoarded 1,500 silver half-dollars, keeping them hidden on his property somewhere “in total disregard of interest or premium.” Until that is, the summer of 1880, when he suddenly began to use them.

Had the old Doctor completely forgotten about his stash and suddenly stumbled upon it? Was he no longer making an income and this was the only money he had? Was it all just an amusing jape on his part, a practical joke some forty-five years in the making?

While we know the “how” of their appearance, the “why” will likely ever remain a mystery.

Aug 9, 1880

A Rave Review?

As mentioned numerous times in these posts, the village whaling fleet had disappeared by 1875. Happily, direct railroad service began in 1870 and the village was able to begin pivoting its collective business focus from being a whaling port to being a summer destination. All it needed was to get the word out.

One unnamed resident of Franklin, New Jersey - evidently a gentleman compiling a travel brochure of some sort - visited the village at about this time and was all too happy to share his thoughts of the place in a letter of this date:

“Sag Harbor is increasing in public favor as a remarkably healthy and accessible summer resort. For this purpose it possesses rare advantages. It is the center of a prosperous farming section, beautifully situated on Gardiner’s Bay, and nearly surrounded by popular island resorts and numerous indentations of the bay. The buoyancy of the atmosphere [and] the complete lack of malaria make the healthfulness of Sag Harbor proverbial… Of the many advantages which this pretty place offers to those rusticating we may mention with pleasure conveniences for fishing, sailing, yachting, bathing and local amusements… In addition to the varied and excellent facilities which the place extends to those seeking health and recreation, the writer is pleased to mention [a] general absence of drunkenness and rowdyism.”

So in sum, for all you budding copywriters out there:

“Visit malaria-free Sag Harbor - Now with drunkenness and rowdyism!”

Pictured: Some alluring malaria-free village sirens.

Introduce your brand

July 21st, 1875: Well Done, Kate!

In the mid-1870s there seems to have been something of a spelling bee fad in America. Some historians credit the craze to the best-selling novel “The Hoosier Schoolmaster,” published in 1871, in which the hero who falls in love with a woman he faced in a “spelling match” as they were usually called at the time (the term “spelling bee” would gain in popularity in the 1870s).

Local newspapers of the time have items mentioning matches taking place in Southold, Jamesport, Riverhead and even as far away as Baltimore (“Amoronthologosphorus” anyone?)

Sag Harbor finally got into the act on this date, with a spelling match held at the Baptist Church. Filled with eager spectators by the 8pm start time, the contestants made their way to the stage – all women, with a few last second additions of gentlemen from the audience.

Captain Banker Havens was the first contestant. He began well enough, but after just a few words he stumbled on “beleaguerer” and was out of the match.

The remaining three men who joined the contest – Mssrs. Payne, Gleason and Lyon – had no better luck with the word than Captain Bunker had, and they too were eliminated. Now only the women remained. Would they fare any better?

Indeed they would, with Miss Nellie Cooper spelling the word correctly. The contest would go on to become quite lively and proved an entertaining evening, until finally there were just two contestants left: Miss Nelson and Miss Kate Cooper. They traded turns until finally Miss Nelson was given a real stumper.

Pronounced “cow-chuck,” it was a French word meaning “rubber,” from the obsolete Spanish cauchuc, which itself was probably from a language of Amazonian Peru or Ecuador.

Miss Nelson gave it her best shot, but failed.

It was now Kate Cooper’s turn. If she got it right, she would be the winner. The audience no doubt sat in hushed silence as she began…

C-A-O-U-T-C-H-O-U-C. “Caoutchouc.”

Well, that’s one way to spell it. The other is… C-O-R-R-E-C-T!

Well done, Kate!

June 12, 1896 – Steamship Shinnecock Goes into Service

The Long Island Railroad opened service to the village in 1870 – but it wasn’t the only way get “here from there.” Long before the railroad arrived there were stagecoaches (the trip to New York took three days), sailing ships (packets) and eventually – steamships.

While certainly slower than a train, steamships offered a very relaxing and luxurious journey. For years, there was an economic rivalry between the Long Island Railroad and the Montauk Steamship Company, which offered service between New York and Sag Harbor, Shelter Island, Greenport, Montauk, and other east end locations.

In a battle of one-upmanship, larger and more luxurious ships were brought into service to lure passengers away from the rails, and there were few ships finer than the Shinnecock. Built in Delaware by the Harlan & Hollingsworth yard, she was 238 feet long with 2 dining rooms, a smoking lounge, 90 staterooms, 120 berths and rated to carry 800 passengers. She was also equipped to carry 60 horses. Interior decorations were white and gold, with oak furniture and plush red carpeting. Being a vessel on the cutting edge, she also featured “a complete electric light and call service” and “perfect ventilation.”

The big moment arrived on this date at 9:30 pm. Throngs were on Long Wharf awaiting her arrival. She did not disappoint. A mile out the ship turned on her electric lights which cast such a bright light they lit up the crowd on the wharf. When a few hundred feet away the steamship Long Island, tied up at the wharf, gave three long blasts of her steam whistle, which were answered by the Shinnecock. The whole crowd cheered as the new ship slid easily up to the wharf.

Mrs. French, wife of the purser Frank French, was quickly lifted over the rails, thereby winning the honor of first person on board.

The Shinnecock and her sister ships evidently proved too much for the Long Island Railroad. Tired of the competition, the railroad men finally figured out a successful strategy: In 1899 they bought the Montauk Steamship Company and began running the ships themselves.

June 8, 1895 – Sag Harbor During The Second Century

In the 1890s the whole country went “bicycle crazy.” Thanks to some recent innovations (safer designs, pneumatic tires and mass production) bicycles suddenly became all the rage for, well, virtually everyone.

While casual rides around the park might have been enough most people, for the hardcore “wheelmen” of the day nothing proved as exciting or challenging as “The Century Ride.”

As the name implied, it was a ride that was 100 miles long. It wasn’t a race, but rather a personal challenge, with riders given just 14 hours to finish – that included mandatory rest stops and lunch, so the pace was at least 12 miles an hour on roads that were sometimes little better than dirt paths. Many “Century Clubs” were formed accepting only riders who had completed such a ride to prove their cycling prowess.

Naturally wanting to end the trip at home, it didn’t take New York City cyclists too long to determine a perfect starting place for a century ride: Sag Harbor. Easy to reach by steamboat or rail, the first Long Island Century Ride (from Sag Harbor to Jamaica) was made in 1894.

On this date in 1895 the second Century Ride was made, with some 200 New York City cyclists arriving at the village on the steamer Shelter Island the night before, and crowded into the American Hotel and Nassau House to eat the hearty meals prepared for them. One hopes they found time to get some sleep as well, as the race would begin the next morning at 5am.

At starting time the cyclists all gathered at the starting line on Main Street, surrounded by throngs of onlookers. “Never before in the history of our village were so many people gathered in our streets at so early an hour,” gushed the local paper, “…except for anything but a village conflagration.”

And then – they were off! The route would take them through Bridgehampton, Southampton, Shinnecock Hills, Canoe Place, East Quogue, Westhampton Beach, Speonk, Eastport, East Moriches, Centre Moriches, Brookhaven, Bellport, Patchogue, Sayville, East Islip, Islip, Babylon, Atlanticville, Seaford, Freeport, Valley Stream, Jamaica and finally Brooklyn (Never mind pedaling the whole route, we’re exhausted just typing it).

We're pleased to report the ride was an unqualified success, with all participants (save two who suffered mechanical problems) making it to the finish line within the time limit, thereby officially becoming “Century Men” – including a 10-year-old boy named Hubert Brennen Jr.

Well done Hubert!

[pictured: Some “Century Men,” c1895]

Mid-February 1912: Baby, It's Cold Outside!

The winter of 1911/12 was one of the coldest the village ever experienced. Starting February 7th, the morning temperatures for the next two weeks never got above 25 degrees; for twelve of the fourteen days it was in the low teens, and often in the single digits. The harbor froze over, making it impossible for sailing ships, or even steamships, to reach the village.

The lengthy cold spell also caused many of the water pipes running into homes and business around the village to freeze. In the Library, water had to be carried in buckets to put into the boiler to keep the steam radiators working. On Sunday, the organs at both the Methodist and Episcopal Churches gave out (they used steam pressure to blow air into the pipes, one assumes.) It eventually got so cold that even the large water mains buried under the streets began to freeze, with the one under Henry Street actually bursting from the cold.

Despite the bitter cold there were glimmers of joy - the snow was cleared from Otter Pond, and on the evening of the 9th skaters and spectators enjoyed music by the Sag Harbor Cornet Band, and by the next week the daffodils and hyacinths were noted as beginning to show their heads.

Spring was just around the corner...

Feb 6, 1849 – Seeing The Elephant, Part II

As discussed two weeks ago, the village was hard hit by “gold fever” in 1849. Various “companies” were formed, the idea being a large group of men working together could make a better go of it in the mines than a single individual. The most prominent local group was known by the very-all-encompassing name of “The Southampton and California Mining and Trading Company.”

In 1850, there were three ways to get to California; you could take a wagon across the (still wild) west; you could take a ship to the east coast of Panama, make your way to the west coast and take a second ship up to San Francisco; or you could sail all the way around South America. For a group of men from a whaling port, the choice was obvious.

Led by ex-whaling captain Henry Green (his brother Barney was also “on board,” in every sense), the group bought the ex-Sag Harbor whaling ship Sabina from her current owners in New York, and fitted her out as fast as possible.

The Sabina cleared Sag Harbor for San Francisco on Feb 6, 1849 with some 90 men on board - company, crew, and passengers included.

Arriving in San Francisco about six months later, the Company quickly set off for the “diggings,” and suffered the same fate as nearly everyone else who went west - untold wealth was not found.

Eventually, most of the men found their way back home; sadder, but perhaps wiser, having seen the elephant for themselves.

Sidenote: The Sabina was not the only ex-Sag Harbor whaling ship to end up in San Francisco. Most famously the ship Niantic, that was part of the village fleet from 1844 to 1847, was turned into a hotel [pictured]. She burned in the fire of 1851, after which an actual hotel building was built on the same site. Remains of the ship were found under the foundation during renovations in 1978.

Mid-Late January, 1849: Seeing the Elephant (part 1)

In 19th century America, the phrase “I have seen the elephant” was widespread, with some experts giving its meaning as “gaining experience of the world at a significant cost.” This seems to have been based on the (perhaps apocryphal?) story about a farmer who hears an elephant is on display at a circus in a nearby town. He decides to go see it for himself but encounters countless hazards and mishaps on the way. He finally gets to see the elephant, but the adventure taught him more than a few life-lessons. If a fellow ever had the misfortune to see an elephant “trunk to tail,” he would no doubt be a sadder but wiser man.

In January of 1849, dozens of Sag Harbor men were about to set off and see the elephant for themselves. News of the discovery of gold in California hit the local papers in September 1848; by the start of the New Year much of the village (indeed, much of the world) was suffering from “gold fever” and making plans to head to the mines. They were closing up their shops, abandoning their careers, and saying goodbye to their families.

As well as carrying the latest news from California, the local papers also carried a multitude of ads from those who had quickly sussed out the truth about the gold rush – that you had a better chance at making good money selling things to the miners than you did by actually going to the mines.

Case in point, Russell S. Wickham, owner of a stationary store on Main Street, whose ad is seen here,

One imagines the quarters were pouring in.

Jan 17,1918: An Editor’s Sad Duty

In a small town, it is all too common for police, fire, and medical personal to deal with tragedies that touch their own homes and families. One other occupation that also falls into that category, though likely overlooked (as we did until coming across this item) is newspaper editor, as this poignant item reveals:

ABBIE J. D. HUNTTING-HUNT

During the fifty-eight years and over, which the editor of this paper has been at the editorial desk, he has written many – very many – articles on the departure of near and dear friends, but never has he written one, during that long period of time, which touched his heart with a firmer grasp than the one he is now called upon to chronicle; and that is the announcement that his wife is dead, she passing from this life to life eternal, in the full belief of the promises of the resurrection, at 11:30 Thursday night last week; having been a consistent member of the Presbyterian church of Sag Harbor since just after her marriage in 1862, and prior to that a member of the same denomination at East Hampton, her ancestral home, when she received that Christian education which she not only so faithfully portrayed in her daily walks and conversation, but in teaching a Bible Class and other classes in the Sunday School for many years.

For more than fifty-five years we have traversed the walks of life together, our hearts have beaten in union as one, our thoughts have blended for each other’s comfort.

Mrs. Hunt has proven herself a kind, affectionate, loving, loyal wife during those fifty-five years. She has been faithful in both her parental and adopted homes.

But finally her life fuel became exhausted, the machinery rapidly slowed down, the wheels ceased to turn; then came death. All we can now further say, is farewell, dear wife, farewell until we meet again.

[Photo from findagrave.com, added by Joy Ann Strasser]

Circa Jan 8, 1873: :

The Iron Horse Rears Its Ugly Head

As mentioned here back in July, after decades of waiting for the Long Island Railroad to build a branch line, Sag Harbor finally got train service 1870. And, as the saying goes, “they all lived happily ever after.” Hooray!

Or not…

Overall, train service to the village was a very good thing. It’s positive effect on people’s personal lives and businesses could hardly be overstated. But there was no denying that the trains also caused problems. There was the noise and smell of course; trains would sometimes hit stray livestock (or people), and the cinders produced by the locomotives often landed in the woods by the rails and caused fires - sometimes very large ones.

For two Bridge Hampton residents - Jetur Bishop and Harmon Woodruff - the Sag Harbor line caused havoc of a more liquid nature. In laying the track from Bridge Hampton to Sag Harbor the engineers built an embankment over Snake Hollow, just north of the Bridge Hampton depot, where the two men lived. With the natural drainage flow now cut off, the engineers installed a six or nine-inch pipe through the embankment to allow water to drain assuming that would do the trick.

It didn’t.

Three years later, a heavy winter storm was followed by a thaw and heavy rain. The small pipes couldn’t handle the overflow and the Hollow began to flood - so quickly that two men and their families had no other option than to flee to their second floors to avoid the rising water. Before it began to ebb, the water on the first floors was some four feet deep. “Out buildings” were also affected; tools, farm equipment, harvested crops and other items were all destroyed. By all accounts, rather than a small pipe, it was thought a two-foot diameter drain was the very least that was needed.

As the paper dryly noted, “It is not unlikely that litigation will grow out of the circumstance.” The railroad may have quietly paid off - no other mention of the event has yet been found.

(Pictured: “Spring Flood” by Claude Monet. Experts universally agree Monet never visited Snake Hollow.)

Jan 1, 1878 - Pennies For Paperboys

It was a tradition in England (and in turn, America) for newspaper carriers to hand their customers a “Carrier’s Address” at the start of a new year. A single printed sheet, it was typically written in verse, and often looked back at the past year’s events; but mostly it was a reminder to the newspaper subscriber of the faithful service the paperboy (as we would call them today) had provided, in hopes that the subscriber would give them a tip.

This was no small thing for the paperboys, as they were often the printer’s apprentice and were typically paid little, if anything, other than being given room and board. They therefore eagerly awaited this yearly tradition in hopes of getting some cash in their pockets and happily, it seems, most customers obliged.

In the Carrier’s Address from the Sag Harbor Express of January 1st, 1878 (pictured in part below, and on display at the Museum!) one verse stands out:

“So many things seem new to me, and very strange I own – Music that’s fifty miles away, is heard by telephone...”

Alexander Graham Bell received a patent for his telephone in 1876 and the first telephone line (from Boston to Somerville) was completed in 1877; in November that same year Thomas Edison patented his phonograph, so these were some up-to-the-minute references of cutting-edge

technology.

We’lll

take this more modern digital technology approach to bring you our own "address" - From all of us here at the Museum, we thank you so much for your support this year, and wish you all a safe and happy 2022!

December 25, 1851: Bah, Humbug!

From the logbook of the Sag Harbor Whaling bark Nimrod:

"Hurrah for a merry Christmas - Laying too in a heavy gale of wind from the WSW. Heading NW and a heavy sea running."

We wish you a better Holiday than that aboard the Nimrod!

December 16, 1872: Lost… And Found

On December 16th, 1872, Sag Harbor resident Richard Smith arrived home.

That might not be very newsworthy to you, but it certainly was for him and his loved ones. Because, you see, he was dead - lost at sea some eight weeks prior.

Smith was a crewman on the steamship Missouri. At about 9am on October 22nd, enroute to Havana during a heavy gale, a fire was discovered onboard. The crew tried desperately to put it out, but within twenty minutes it was clear the ship would be lost. The fire made it impossible to reach all the lifeboats; only three were launched. Of these, one swamped immediately, one overturned and drifted away with two crewmen clinging on for their lives (it was assumed they would soon drown) and the last remained near the ship for as long as possible, but due to the rough weather was unable to rescue anyone else from the ship.

Against the odds, Smith was actually one of the men in the last boat. After being tossed and turned for a few hours by the storm, carried further and further away from the burning ship, they encountered the overturned boat that had been swept away earlier – miraculously, the two crewmen were still clinging on. With great self-sacrifice, Smith swam over and helped turn the boat upright, giving the men a far better chance to survive; ironically, almost immediately, one of them was washed away and drowned.

This left Smith and the other crewmen (named Alfred Stewart) in the boat. Soon the winds and seas separated the two lifeboats. Smith and Stewart were now on their own – two against the ocean.

By early evening, the other lifeboat actually managed to made landfall in the Bahamas with a total of seven passengers and five crewmen on board. The other 80 or so passengers and crewmen were lost – Smith and Stewart amongst them.

...Or so it was thought.

Smith and Stewart actually managed to survive the storm and by morning, began to paddle as best they could in hopes of spotting a passing ship. Eventually they managed to cobble together a sail made out of the canvas taken from life preservers; sailing was easier than rowing but did nothing to quench their thirst or hunger (they had no food or water), nor would it protect them from the many sharks. On the third night, Stewart fell overboard, and Smith, despite his weakness, and the sharks, dove overboard and rescued his companion. On the fourth day they finally saw a sail but – heart wrenchingly - could not make themselves seen or heard, and the vessel sailed on without stopping. Three more days of unspeakable deprivation passed until finally, on their eighth day in the lifeboat, they sighted land.

It proved to be Walker’s Key: Wild, barren, and without any vegetation. Smith and Stewart were able to land their boat, barely having the strength to crawl over the rocks to shore. They found prickly pears and spider crabs, and a little rainwater in the rock depressions. After three days, they had the strength to build a crude hut out of driftwood and seaweed, and erected an oar with a strip of canvas flying from it as a distress signal to attract any passing vessel. They could do nothing more now than try to survive and wait for rescue.

Sadly, Stewart didn’t make it. He died of thirst and hunger about a week later.

On the sixteenth day, rescue finally came as a passing schooner saw the distress flag and picked up Smith, who was found on the rocks by the shore, too weak to even move. He was brought to Green Turtle Key and, when able, took a schooner to Nassau and finally a steamship back to New York.

The news of the disaster (which included a list of survivors, Smith not among them) was printed in New York City papers by October 31st, and the Sag Harbor paper reported the disaster and Smith’s death on November 2nd (five days before his rescue) so his friends and family were certainly mourning his loss for more than a month when a cable from Bermuda announced his survival, which was in turn published in local papers by December 12th.

Having survived fire, storm, sharks, hunger, thirst, hopelessness, and found on the brink of death, his arrival home on December 16th must have felt like nothing less than a miracle.

Dec 8, 1859: Let There Be Light

In the 1800s (and earlier), if you wanted to light the interior of your home or business you had three options: An open fire, a candle, or an oil lamp. This was very good news for a whaling village, as whale oil was used in lamps of all kinds (including streetlights and lighthouses), and spermaceti candles were made from the “head matter” of sperm whales.

As the century progressed, two new forms of lighting came into use: kerosene (which began to replace whale oil in lamps) and something called “gaslight” – a light produced by burning the gas that was created by heating coal. But gaslight needed some serious infrastructure: The gas-producing coal furnaces, a huge tank to store the gas, large pipelines installed under the streets, branch lines from the main to each customer, and finally individual lines running to each lighting fixture. These high costs meant that gas service was mostly confined to large cities where there would be enough customers to make the investment pay off.

But this didn’t stop Captain David Congdon. Having closed his steamboat line, he obtained a 25-year gas franchise and began task of bringing gaslight to Sag Harbor. He bought the old Howell candle factory on West Water Street and began converting it into a gas plant. In August, as it neared completion, gas mains were buried under the streets, pipes run to buildings, and fixtures installed. Finally, the great day – or rather night – arrived. On December 8th 1859, as darkness fell, each customer turned on their burners. Would the system work?

It did, and Sag Harbor became just the second village on all of Long Island to have gaslight (the first being Brooklyn). As described by the local paper, “illumination” spread rapidly up Main Street, the dazzling effect “better imagined than described…Troops of youngsters, and some old people too, paraded the streets, gazing with wonder at the brilliant display, and giving vent to their enthusiasm in repeated cheers for gaslight and Captain Congdon… What was dark and gloomy before, now becomes brilliant and cheerful…”

The thoughts of the village whaling captains were not recorded.

[Pictured: "The Big Blue Ball," the last vestige of gas service in Sag Harbor. Situated west of the (current) post office, it was built in 1931, and dismantled in 2006.]

Nov 29, 1818: A Close Call

On November 29th 1818, Sag Harbor whaling ship Abigail (Captain Post) was off the coast of Brazil. Having spotted a whale, the boats were lowered and the chase began. One of the boats was able to “attach” to a whale. Feeling the sting of the harpoon, the whale took off like a shot, swimming as fast as it could to get away from the danger – not knowing of course that a rope was attached to the harpoon, keeping the boat within striking distance no matter how fast it swam. All the crew had to do now was hold on tight and let the whale tire itself out, and the hunt would be a success.

Suddenly - disaster. The rope snapped. The sudden jolt threw Captain Post and another crewman into the water as the rope (still attached to the speeding whale) snaked over the rest of the boat. It wound itself around the leg of crewman Eli. P. Halsey and he was yanked overboard in an instant. The whale – now free – dove for safety, pulling Halsey under the waves. His journal entry describes what happened next:

“I gave myself up as inevitably lost, when suddenly I perceived the line [began] to slacken round my leg. I instantly shifted the turns off with my hands and began to ascend. When I reached the surface of the water [the men in the boat] luckily perceived my head and hands, as I could not swim.”

Halsey was pulled from the water and brought back to the ship where Captain Post and the others made him as comfortable as possible. Though in great pain, happily, amputation was not necessary. Over the next few days the cook (“Old Oakes”) dressed the wound with “wormwood soaked in rum and sugar.”

By December 6th Halsey was strong enough to hobble about on deck without assistance. That same day the ship was able to take a whale, which seems to improved Halsey’s mental state as well. “In fact,” he noted, “getting this whale puts new life into all of us.”

Happy Birthday to You!

Ephraim Byram: Born November 25, 1809

Last week we focused on the Second Great Fire of Sag Harbor (1845), and how it could be seen as dividing line of sorts between “old Sag Harbor” (with an economy based around the whaling fleet) and “new Sag Harbor” (a factory town). And if there is one person who might personify this shift, it would be Ephraim Byram (1809-1881).

As the village whaling fleet grew in the early 1800s and became the primary economic engine of the village, a whole host of small, independent tradesmen sprang up as well: carpenters, boat builders, sail makers, caulkers, riggers, blacksmiths and others. Byram was among them. The son of a carpenter, he learned how to maintain and repair chronometers, compasses, and other nautical instruments for the whaling ships, eventually manufacturing his own (A “box compass” made by Byram, used on a whaleboat, is part of the Museum’s permanent display). He also became “Mr. Fix It” for the village, with residents bringing him all sorts of repair jobs, everything from watches to umbrellas to accordions – Byram could repair them all.

In 1836, he won a gold medal (also on display) at the American Institute Fair for his room-sized orerry; a gear-driven mechanical model of the solar system. He was all of 26 years old.

This led to a commission in 1838 from the Sag Harbor Methodist Church for a steeple clock. Finishing that, he went on to build many more tower clocks all over the country, including for New York City’s Town Hall and West Point Military Academy.

By 1850 as the whaling fleet began its decline, the village needed new economic avenues. A cotton mill opened in the village that year, providing employment for about 175 people. Also opening that year was a brass foundry started by John Sherry called The Oakland Works (situated where Oakland Cemetery now stands). For his factory manager he chose Byram, putting him at the very forefront of the village’s shifting economic character. Byram would eventually become a partner in the firm, and the Works were expanded to include his clock manufactory, becoming known as The Oakland Brass Foundry and Clock Works.

While there would always be numbers of independent tradesmen and craftsmen, the following years would bring various other factories to the village (some more successful than others) as the whaling fleet continued to shrink and finally disappear altogether by 1875. The Factory whistle had replaced the Bosun’s whistle, and Byram - evolving from repairman and clock maker to factory manager and partner -witnessed it all.

[Portrait of Byram by Hubbard L. Fordham, in the Museum’s collection]

NOV 14, 1845

The Second Great Fire

The night of the November 13th was remarkably fine with little wind, bringing to an end (as we saw in our last post) a week that could only be called “routine.” As the villagers one by one snuffed out their candles and went to bed, there was absolutely no hint of the incredible tragedy that was about to occur.

Midnight came and the 14th of November began. At about half past the hour, in a “commission room” in the Suffolk Building full of furniture and other goods, a small fire began. This was the same building that housed Oakley’s Hotel and, in what must have been a rather alarming shock for the hotel guests, the entire building was ablaze within minutes. The three village fire companies were called out to begin what would turn out to be a long, desperate, losing battle.

The fire jumped from the hotel to the Huntting’s store and then to the three dwellings west of it; It crept down towards the wharf, jumping from structure to structure until there was nothing left to burn. It spread down both East and West Water Streets (now Bay Street and Ferry Road)… up Division Street… up Main Street. Though bravely trying to halt the spread, the firefighter’s equipment just wasn’t up to the task. It became a relentless sheet of flame, devouring store after store, workshop after workshop, home after home. At one point it was estimated that forty or fifty buildings were in flames at the same time. For twelve long, brutal hours the fire raged out of control. Some people were able to save their goods or furniture from a burning building, only to have to keep moving it further and further up the street as the flames advanced.

By morning, nothing remained of lower Main Street except ash. Miraculously, there was no loss of life, but close to 100 shops and dwellings were destroyed, along with many barns, stables, sheds, and other “out buildings.” With winter fast approaching, some 40 families were forced to scramble to find somewhere to live.

Just as their parents had done after the great fire of 1817, the villagers quickly began to rebuild with grit and determination. The village would rise again, and relatively quickly – but it would never be the same. The whaling industry, for so long the economic heart of the village, had begun to fail. The village fleet - having reached its apex with 64 vessels this very same year - began its slow decline, and the village itself began its slow and sometimes painful transformation from a whaling port into a factory town.

Nov 5, 1845: The same old, same old

Here’s some of what was going on in Sag Harbor between November 5th and November 11th in 1845:

On the 5th, the temperature at 11am was 48 degrees… Merchant H. L. Jessup urged those who had not yet purchased their fall and winter goods to visit his store at once for great deals, as he was “contemplating a removal” and all his goods must be sold…. Miss Sabina T. Bill lost her black worsted shawl somewhere between the homes of Henry R. Harris and Captain David Loper, and offered a reward for its return… If it turned out her shawl was lost for good, she could always go down to the shop of C. A. Gardiner who carried cashmere, stradilla, kabyle, rob-roy and various other styles of shawls… Dr. Miles, who had just taken over the office and medicines of the late Doctor Sweet, was ready to attend all calls in the line of his profession, day or night…. On the 6th, the sloops Cabinet and Emily arrived from Albany with lumber for S. S. Smith and Co., and W H. Nelson…Beaver-cloth overcoats were available at Gardiner & Sealey’s store for as low as $5…Bottles of Connel’s Magical Pain Extractor were available at the offices of the Corrector, intended to cure chilblains, galls, chaps, whitlous, barber’s itch, ague in the face and white swellings…Ephriam Byram, recently named agent for Bliss & Creighton Chronometers, now had them for sale, along with charts, sextants, quadrants and other nautical instruments…The packet boat Cinderella, Thomas Bennet master, ran to Southold on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday morning, returning the same afternoon.

Pretty dull, huh?

Why are we exploring such mundane matters? Because although they didn’t know it yet, this would be the last mundane week the villagers would have for some time - as next week’s post will show…

October/November, 1909

Warning: Banana Peel Ahead

Today we’ll get a bit more metaphysical than usual, and take a look not at a specific event, but rather a theme: Humor. Or to be more precise, humor circa 1909. What can comedy tell us about a time and place? These jokes (if that’s not too strong a word) are presented verbatim as found in late October/Early November 1909 issues of the Sag Harbor Express. The Editor would have gathered these from other newspapers and magazines from the day, so presumably they are examples of what he found funny – or at the very least, what he thought his readers would find funny..

By this time, vaudeville and burlesque had emerged, overtaking the minstrel shows that were previously so popular and prevalent; all three would help form the foundations of what would eventually become known as “stand-up comedy.”

While stilted to our modern ear, with a close reading you might just see the primordial glimmers of Abbott and Costello’s back-and-forth banter, the self-deprecating stylings of Henny Youngman, the observational musings of Jerry Seinfeld, and the out-and-out stupidity of Homer Simpson.

Or, you might just groan..

First Art Student: Do you know how to make a Maltese Cross?

Second Art Student: Yes - pull his tail..

Barker: Say, you talk to me as if you thought I’m an idiot!

Parker: Pardon me – I’m always giving myself away.

Math Professor: You should be ashamed you yourself. When George Washington was your age he was a surveyor.

Student: And when he was your age, he was President of the United States.

Mrs. Buggins: (sniffing suspiciously) John, you’ve been drinking!

Mr. Buggins: Well, you see, I walked home so fast that I had to stop in the saloon on the corner to catch my breath.

“Was that you scolding a poor dog who was merely indulging his natural inclination to howl at the moon?” asked the kind-hearted man. “Yes” answered his neighbor. “Don’t you know you ought to be kind to dumb animals?” “That dog isn’t dumb, he’s only deaf.”

“So your daughter has been to cooking school?” “Yes,” answered Mrs. McGuley. “I suppose she has helped along the household economics?” “Not exactly. She has made us appreciate our regular cook so much that we have to raise her wages every time she threatens to leave.”

Examining Magistrate: “Madam, you persistently deny that you committed this act, though the description of the culprit fits you exactly: beautiful face and figure, extremely youthful appearance, most attractive –

Defendant: Your Honor, I confess all – yes, it was I!

She: But have you any prospects?

He: Only you and one other girl.

“Your wife is very sick, Mr. Miller. She should not talk so much.”

“Why Doctor, I’ve been giving her the same advice for the past twenty years.”

Oct 28th, 1900: "L'chaim!"

By the 1850s it was becoming clear that whaling was no longer a “going concern” (to use the parlance of the time). The village began to cast about for other economic options; over the next three decades cotton mills, flour mills, brick making, a broom factory, a pottery factory and even a sugar refinery were all tried, all with varying degrees of success or failure – mostly failure. A more secure economic footing was finally achieved with the establishment of the Fahys Watch Case factory in 1883.

New enterprise brought new faces. Many of the craftsmen employed at the factory were Jewish immigrants with Russian, Polish and Hungarian roots. As livelihoods and living spaces became more secure over time, their thoughts eventually turned to their spiritual wellbeing. In 1890 land was purchased for a Jewish Cemetery, and in 1896 land was purchased for a Temple. Although services were held in the building in 1898 to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, Temple Mishcan Israel didn’t have its formal dedication until Sunday October 28, 1900.

Several hundred invitations had been issued, and despite the steady drizzle, a large crowd gathered outside the Temple over an hour before the start of the ceremonies. At 2:30, Jacob Meyer of Riverhead opened the synagogue; David Sandman of Riverhead carried the Torah to the ark; Morris Meyer of Sag Harbor lighted the light, and Nathan Meyerson of Sag Harbor made the blessing. Over the alter was a six-pointed star made of red and yellow roses, festooned on each side by American flags.

The Temple exists to this day, having changed its name in 1948 to Temple Adas Israel.

October 16, 1862:

"The Saddest Day"

During the American Revolution and the War of 1812, the village of Sag Harbor was on the “front lines,” suffering British attacks in both conflicts. During the Civil War however, the village had every reason to expect to remain something of an idyllic backwater.

Sadly, a horrific war-related tragedy would shatter the peaceful little village.

In October 1862, Union General Charles T. James brought a small party of foreign military observers to the village to witness the test firing of his “James Projectile” in hopes they might want to purchase it for their own armed forces.

Unlike a round cannon ball, the James projectile was an elongated cylinder, more like the shape of a modern bullet. It weighed about twice as much as a cannon ball of the same diameter - which meant getting more destructive power per shot without having to buy a larger cannon. No wonder other armies were interested.

As Russian and French officers observed the test firings taking place on a bluff near Conklin’s Point, one shell refused to fire. General James removed the cap of the shell to inspect the inside and realized that the internal mechanism (called the “plunger”) was stuck. He tried to jiggle the plunger free by turning the shell upside-down and banging on the bottom with his hand, with no luck. James then asked the gunner Mr. Beverland to take a pair of pliers and help pull the plunger free.

Tragically, Beverland’s attempts to free the plunger instead made the shell explode.

To give you some idea of the power of the blast: a piece of the errant shell weighing a 1.5 pounds hit the side of the Mansion House hotel – about a quarter of a mile away.

The blast would claim five lives: Beverland, Captain James Smith, a French officer named Kreutzberger, and General James himself, who died the next day. Orlando Bears, an onlooker, died a week later from his injuries. At least nine others were wounded.

The local paper described it as “the saddest day which this community has ever witnessed.”

[pictured: A James Projectile]

Oct 10,1910: Check It Out!

Today we celebrate another birthday of sorts – that of the John Jermain Public Library, which formally opened its doors on October 10th 1910. (Happy 111 years!)

Funded by Mrs. Russell Sage, the grande dame herself came out for the opening ceremony from New York City by automobile; a mode of transportation evidently still so uncommon in the village that the fact was noted upon in the newspaper.

With Mrs. Sage and the official staff present – Librarian Mrs. Olive Pratt Young and her assistant Miss Virginia O’Brien - a short dedicatory prayer was offered, after which the “giving out of the books” commenced. They could be kept for 14 days. A late fee of one cent per day would be charged. By the end of the first day some 250 books had been checked out, and a further 137 library cards issued, bringing the total up to 719.

Three months later – in January 1911 - an astonishing total of 5,779 books were checked out. At the time, the library only housed 5,000 books in total, so to say it was popular success is something of an understatement. A further 1,896 books were added to the collection in its second year.

Our post today would be full of nothing but celebration, if not for the recent news that current Library Director Catherine Creedon will be stepping down at the end of the year. Having led the Library for the past fourteen years – not only through a massive construction project but also through two years of a pandemic – her professionalism, steady hand, buoyant attitude and grace under pressure will surely be missed.

Director Creedon; we from across the street salute you!

Happy Birthday To You!

Captain Mercator Cooper: Born Sep 29, 1803

This week we say Happy Birthday to Mercator Cooper, a whaling captain out of Sag Harbor who is credited with not only the first “formal” American visit to the (then) closed country of Japan, but also the first documented landing on mainland Antarctica.

Born in Southampton, Cooper was the child of Olive Howell and Nathan Cooper. He shipped out on whalers in the 1820s, and worked his way up to captain by 1832; he was captain of nine voyages in total from 1832-1855.

When captain of the ship Manhattan in 1845, Cooper rescued 22 shipwrecked Japanese sailors in the Bonin Islands and - despite Japan being an isolationist nation and closed to all foreigners - chose to sail to Japan and repatriate the shipwrecked men. Outside Edo Bay (Edo was the capital, and is now known as Tokyo) Cooper waited as four of the Japanese sailors went ashore and explained the situation to the authorities. On April 18th, an emissary of the shogunate gave Cooper permission to anchor in the Bay. Cooper and his crew were the largest number of foreigners allowed so near the capital city in over 200 years. The Japanese were friendly, with several nobles coming on board to examine the ship. There were limits to the hospitality however – none of Cooper’s crew were allowed on shore, and all weapons on board the Manhattan were confiscated during their stay. The Japanese were particularly intrigued by Pyrrhus Concer, the only African American on board, as well as by a Shinnecock native named Eleazar.

Providing the ship with ample provisions, and with gifts and a letter from the Shogun for Cooper himself, the Japanese sent the Manhattan on her way – with stern warnings to never return under penalty of death, even if they found more shipwrecked sailors.

Admiral Perry would make his famous visit to “open” Japan in 1853.

Cooper was the captain of the ship Levant making a whaling-and-sealing voyage that left Sag Harbor in 1851. In January 1853, after making a quick passage through the pack ice in the Ross Sea, Cooper sighted land – high mountains 75 miles or so behind a huge ice shelf. A boat was launched and landed on the ice, but no seals were found. The landing occurred on what is now called the Oates Coast of Victoria Land, and is considered “the first adequately documented continental landing" on mainland Antarctica.

Not too shabby for a Southampton boy who wasn’t even trying!

Sep 21, 1938: The Long Island Express

With the recent near-miss of hurricane Henri, our post today is quite timely: A look back at the Hurricane of 1938, which hit Long Island with full force. This post was written by our summer employee Charlotte Robertson, who has now gone off to her freshmen year of college. Best of luck Charlotte!

Nicknamed the “Long Island Express” due to its incredible speed, the Hurricane of 1938 was one of the worst natural disasters of the 20th century to strike the northeast, and the ruin to Sag Harbor was significant.

On September 21st, at around two in the afternoon, the Sag Harbor schoolhouse was in full session when the hurricane hit the coast of Long Island. The students, being kept in the building to wait out the storm, watched as every window shattered from the high winds. Glass breakage was one of the primary problems in Sag Harbor; down Main Street, flying glass from broken storefronts injured several passersby.

Several buildings were damaged, including the house next to the Whaling Museum. More than a hundred chimneys throughout the town were torn to the ground. The theatre and the Post Office lost their roofs. The Episcopal Church endured damage to its steeple and shingles. A handful of houses were crushed by debris.

The most notable damage was the 185-foot spire of the Old Whaler’s Church, which was blown off. Built in 1844, it has been said that the church’s spire was so tall that it became a landmark for whalers returning home, as it could be seen from the ocean. It has never been restored.

The storm’s impact was unfortunately during high tide, making Sag Harbor especially vulnerable to flooding. Two boats anchored in the harbor were wrecked. Rowboats glided down the streets to rescue residents from their homes.

The hurricane also created a widespread blackout, preventing all telephone communication. The village was also physically isolated for several hours, the roads being blocked with debris, especially fallen trees.

The loss of trees was widespread. Oakland Cemetery was hit particularly hard, with reported hundreds of trees littering the ground amongst upturned headstones. Fallen pine trees buried the lawns of the John Jermain Memorial Library and the Pierson High School. Five trees fell into Otter Pond. And throughout town, residents mourned their now-empty backyards. As noted by the Sag Harbor Express: buildings can be rebuilt but restoring the village’s beautiful tree population would take half a century.

With modern weather radar and communication systems, Hurricanes can no longer catch us unaware – only unprepared.

Sep 15, 1884:

Rum and Enthusiasm

One might think drunk driving wasn’t really a thing until the invention of the automobile – not true! - as this item from the Sag Harbor Express reveals:

“At about 6pm, a vehicle containing two men filled with rum and enthusiasm dashed down Main Street at a furious pace. The horse turned into the yard of the Nassau House, overturning the wagon, and hurling the occupants to the ground with much force. One man escaped injury; the other was badly cut and bruised about the face and head. The cause of the disaster was quickly drawn from the pocket of one of the men and applied to the head of the wounded one, who soon recovered sufficiently to exclaim “Don’t put too much on,” evidently preferring the internal to the external application. The man was patched up at Lobstein’s Pharmacy; the wagon wasn’t worth it.”

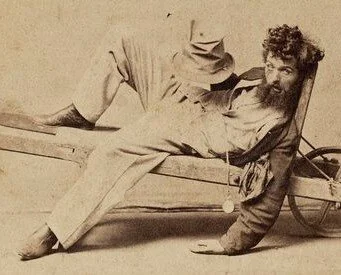

Pictured: “The Five Stages of Inebriation” (Stage 4) – a set of five photographs by comic actor C. P. Pickering (c1860s)

Happy Birthday To You!

Mrs. Russell Sage: Born Sep 8, 1828

Today we take a break from “straight-up” history to give a birthday shout out to Mrs. Russell Sage, or, as she was sometimes known in Sag Harbor, “Lady Bountiful.”

Margaret Olivia Slocum was born September 8, 1828 in Syracuse NY, the daughter of Margaret Pierson and Joseph Slocum. She went on to become a teacher in her hometown, and after the Civil War a governess in Philadelphia.

In 1869 she married Russell Sage, a financier / railroad executive. When he died in 1906 he left his $70 million dollar fortune to his wife with no conditions. Suddenly one of the wealthiest women of her time, she quickly turned her attention to philanthropy, often focusing on the well-being of the poor, education, and expanding opportunities for women.

As the birthplace of her two grandfathers (John Jermain and Samuel Pierson), Sag Harbor had a special place in her heart. In 1908 she purchased the old Benjamin Huntting house (now home to the Whaling Museum) to use as her “summer cottage,” and over the next two years turned her philanthropic eye on the village, donating funds to build a new railroad station, Mashashimuet Park, the John Jermain Public Library, and Pierson High School.

She passed away in 1918; the Park, Library, School remain vital institutions in the village more than one hundred years after her death - a testament to her forethought, largesse, and love of the village.

c Sept 2nd, 1901: Edgar Gets Angry

Standing at the intersection of Main and Madison (in “Madison Square” as it was once called) is a monument to those village men who served in the Civil War. It was funded by the Ladies Monumental Society and the unveiling ceremony took place with suitable fanfare in October 1896.

Edgar Z. Hunt was a Civil War veteran himself. Born in Sag Harbor (son of Col. Harry Hunt, the founder of the Sag Harbor Corrector) the younger Hunt was both an insurance salesman and surveyor; his reputation and expertise in the latter field evidently known up and down the Island.

By 1901 he was 79 years old, possibly in ill health, and definitely ornery. “I have been guyed of late when downtown,” he complained in a letter published in the Corrector, “about the grade and placing of the iron fence around the soldier’s monument on Madison Square.”

Hunt had been hired by the Village Trustees to survey the plot in preparation of the building of the fence, and he was none too pleased to see the fence company had made such a mess of things. On the north side of the plot the grade fell three inches; instead of taking this into account to keep the top rail level, the fence was instead built to follow the slope. Further, the northwest corner should have stood nine inches about the grade; instead, it was fifteen. In fact, the entire fence was out of plumb and out of alignment. It wasn’t just Hunt who was irritated; another leading citizen said the fence looked “as if it had been dumped from the dray and left as it landed.” Clearly, something had to be done.

And so it was, seven months later… when the fence received a fresh coat of green paint.

Exactly who thought this might resolve the issue – or, in fact, be of any use at all - is not known; but clearly the Village (and no doubt Hunt) remained unhappy. By the next month steps were finally taken to lower the height of the fence, put a concrete coping beneath it, and grade the entire plot properly – in short, everything Hunt had proposed to the Village back when he surveyed it.

So finally, six years after it had gone up, the Corrector was able to report the monument had the “finished appearance, which it should have long since possessed.”

Hunt died three years later in 1905; one hopes, at least, a slightly happier man.

[PICTURED: A postcard circa 1905 showing the monument and a proper looking fence.]

August 26th, 1839: A suspicious looking vessel

Captain Henry Green was one of Sag Harbor’s most noted and successful whaling masters. Aside from his storied whaling career, he is also known for helping repel the British raid on Sag Harbor during the War of 1812, and for leading a company of fortune seekers out to California during the Gold Rush of ’49. But on August 26th 1839 he made history of a different sort.

On this date Green and his friend Captain Peletiah Fordham were out in Montauk hunting by Fort Pond Bay when they came across four African men dressed in nothing but blankets, only one of whom knew a very little bit of English. The men asked what country they were in, and if was a slave country. Four other black men soon joined them, and eventually they made it clear they wanted Captain Green to come aboard their ship (which was lying off Fort Pond Bay) and sail them to Sierra Leonne. For his services, they would give Captain Green a great deal of money that they had on the ship. Slightly suspicious, Green suggested instead the ship be brought into port. As night was approaching, the men refused, but agreed the ship could be brought to port the next day. Green then asked for proof he would be paid. Some of the men went back to the ship and returned with two trunks. Upon opening them, Green found himself staring at over 400 Spanish doubloons.

It is hard to imagine how history might have changed that day if Green and Fordham had encountered these men a little earlier in the day, or even if the wind had been blowing from a different direction. As is was, the US Revenue Cutter Washington sailed into view and took control of the situation, with her commander Lt. Gedney seizing the “suspicious vessel,” the Africans and the chests of gold as well, leaving Captain Green empty handed.

Although arguably the first on the scene, Captain Green would become a mere footnote in time, as the story soon became an international affair that would change the course of American history.

The name of the vessel was - the Amistad.

August 15, 1881: An Incendiary Event

As discussed last week, the whaling industry hit some hard times between 1850 and 1865. Whaling out of Sag Harbor (as covered in our July 16th post) came to an end in 1874 when the brig Myra – the last vessel left in the fleet – was condemned in Barbados.

By the 1860s, the village was desperate to find new industries. Many were attempted, most with modest success at best. In 1875 another contender arrived, when William Jones and Frederick Wood of New York City made plans to start “The East End Pottery Works.” Given generous terms, they settled on a site in Sag Harbor. A million bricks were delivered to construct the factory. Excitement surged throughout the village as the promise of a new industry became reality.

Unfortunately, work on the building would drag on for some time. Although construction began in 1876, it wasn’t until 1880 that all the necessary machinery was delivered and installed and the final touches on the buildings were nearing completion. By this time, ownership had passed to P.C. Petrie, who announced the factory would open in August 1881.

But instead of opening – disaster. An arsonist put the place to the torch. Despite the efforts of the village Fire Department an enormous fire, set in three different places, engulfed the building.

It was a crushing blow to the village. An industry on the verge of opening - that might have gone on to employ hundreds - was instead turned to ashes. The damages were calculated to be about $6000. Petrie offered a $250 reward for any information leading to the arrest of the person responsible, and vowed the factory would be rebuilt.

It never was.

The culprit was never caught, and the reason why it was burned down remains a mystery.

August 10, 1866: Lost

By 1866, the American whaling industry was in an irrevocable downslide, having suffered a series of major blows in the previous twenty years: First, by the 1840s the Atlantic had been overfished, forcing whaleships to sail to the more distant oceans to find their prey. While a ship could still come home with a full cargo, all the costs of a longer voyage meant less profit- or none at all. Then, in 1849 the California Gold Rush lured away the adventurous sort of men who might have otherwise signed up for a whaling voyage. Thirdly, oil was discovered in Pennsylvania in 1859, and while it would take some time for that industry to mature, it was obvious that oil from the ground was the future. And lastly, the Civil War caused both a labor shortage and a dangerous environment for any Yankee whaleship, as Confederate raiders roamed the seas looking to capture prizes.

The Sag Harbor fleet suffered through all of these fates, and the effect was dramatic. From its height of 63 vessels in 1845, by 1866 the fleet was down to just 13.

One of the remaining vessels was the bark Ocean. She had made two previous voyages out of Sag Harbor, neither very successful, but now that the Civil War was over the entire fleet, despite its diminished size, likely had high hopes. In command was Captain James Hamilton.

The rest of the crew was 1st Mate Samuel R. Reeves; 2nd Mate William Fowler; 3rd Mate Jeremiah G. Loper; Boatsteerers (aka Harpooners) Edward Fowler, J.A. Fields and John Roderick; Cook Thomas Aldridge; Steward Thomas Higgins, and crewmen R. B. Vernon, Alex Schultz, P. Mertz, G. Stertof, W.A. Bachr, F. J. Morgan, A. McDonald, Edward Parker, Edward Parker, A. Bronge, H. Dugan, T. J. Seeley, W. J. Johnson, S. A. Howard, Thomas Lee and Bob Kanaka.

She sailed on August 10th, 1866… and was never seen or heard from again.

It is presumed she went down in a gale.

July 31, 1789: Enter Here.

Having won the American Revolution and gained independence from Britain, the young nation of the United States found itself… well… broke, mostly.

To raise funds, Congress passed the Tariff Act of 1789 which authorized the collection of duties on imported goods. As there was no income tax at the time, these fees would make up a good percentage of the Government’s revenue. Four weeks later, the US Customs Service was formed, and ports of entry were established - locations where ships from foreign ports would have to anchor so the value of their goods could be determined and the customs duties paid. One of those ports was Sag Harbor, which served as the port of entry for all of eastern Long Island.

The first Customs Collector for the village was John Gelston of Bridgehampton; he was succeeded by Sag Harbor resident Henry P. Dering (pictured below) who, you may recall, was also instrumental in the efforts of getting the first village newspaper up and running (see the post of May 7th).

Dering’s commission as ‘Inspector of the Revenue’ is one of the Museum’s most cherished items, and is signed by... well... some rather notable people.

Who, you ask? Come visit and see for yourself!

July 23, 1840

Monuments, in stone and word

Whaling was a dangerous occupation. Going after a 50 or 75-ton animal in a small wooden boat was a chancy operation at best. Once they felt the sting of the harpoon, whales often turned to attack the boats that were attacking them. They might breech and fall back onto a boat, crushing it, or rise from the depths and ram a boat to pieces. Many men were injured; many were killed.

Such was the fate of Captain John E. Howell, who was killed on this date by a sperm whale off Rotuma Island (now part of Fiji). He was just 27 years old. His three brothers - Nathan, Gilbert and Augustus - were all involved in the business and financial end of the village whaling fleet.

Sadly, Howell was not the first Sag Harbor whaling captain to be killed by a whale, nor would he be the last. His death inspired his brothers to build a memorial honoring all the whaling captains of the village who met the same fate. Located in Oakland Cemetery (on Jermain Street) it is called The Broken Mast Monument, and definitely worth a visit.

Herman Melville, too, erected something of a monument to those lost while pursuing the leviathan, in his masterpiece Moby Dick:

“For God’s sake, be economical with your lamps and candles! Not a gallon you burn, but at least one drop of human blood was spilled for it.”

July 17, 1871

Not with a bang, but with a whimper

In 1845 the Sag Harbor whaling fleet reached its peak with 63 vessels in service. But the ensuing 25 years would not be kind. The rising use of kerosene ate into the whale oil market; the Gold Rush of 1849 made it almost impossible to find crewmen; the discovery of petroleum in 1859 would further erode the oil market, and Confederate raiders during the Civil War (1861-65) targeted Yankee whaling ships.

By 1871 the village “fleet” consisted of just one vessel; the brig Myra. Not only was she the last, but at 116 tons she was one also of the smallest vessels to have ever served in the fleet

Owned by Hannibal and Stephen French, the Myra was readied for to go to sea once more. In command was Captain Henry A. Babcock; her three mates and cooper were also local men. But of the other 18 crewmen aboard, not a single one was from Long Island. After 25 years of uncertainty and decline, the local men had all moved on to other professions.

She departed July 17th 1871 - - and as it turned out she was the last whaling ship to ever sail from Sag Harbor. And she would never return. After being at sea for 41 months she anchored in Barbados in December 1874, too old and worn and rotten to even make it back home. The Captain and crew all returned on board other ships.

And that, as they say, was that.

After some 110 years, Sag Harbor was a whaling port no more.

JULY 12, 1907 :

The Cornerstone Laying Ceremony of Pierson High School

By 1905, the old Union School Building in Sag Harbor had been condemned by the State Education Board. A new building was desperately needed, but how to pay for it? Mrs. Russell Sage to the rescue! Having inherited her financier-husband’s fortune upon his death in 1906, Mrs. Sage then engaged in philanthropic endeavors all around the country – including in Sag Harbor, home to her Pierson and Jermain ancestors. Mrs. Sage offered $100,000 to help build the school (hence the name "Pierson High School")

Land was purchased on Latham Hill and the site was staked out in April 1907. The Cornerstone laying ceremony took place on July 12th. Just after 1pm, the village school children assembled at the Union School. At 1:30 they formed a line and, led by the Sag Harbor Coronet Band and with Fire Department Chief George A. Kiernan as procession Marshall, they marched to the site of the new school where a crowd of some 2,000 people had gathered for the ceremony. Mrs. Sage, evidently too ill to attend, was represented by her brother Colonel J. J. Slocum.

After an opening speech by Board of Education member William C. Green - - and the singing of “America” by the children - - and a prayer by Reverend M. Y. Bovard - - and a speech by District School Commissioner Charles H. Howell - - it was finally time for Col. Slocum to lay the corner stone using a special engraved silver trowel made for the occasion by the Fahy’s Silver Works in the village.

Evidently not willing to let the occasion end on such a fitting and climactic moment, there then followed a speech of “very interesting historical data” given by Board of Education Secretary H. B. Sleight - - and some more music - - and then a “very appropriate" address by the Reverend John Joy Harrison - - followed by the singing of the long meter Doxology - - and the benediction - - and (finally!) three hearty cheers given for Mrs. Sage.

Brevity may be the soul of wit, but it evidently had no place at a cornerstone laying ceremony…

July 4th, 1845:

CELEBRATING AT SEA

From the logbook of the whaleship Thames II of Sag Harbor

July 4th, 1845:

Latitude 49.30 N, Longitude 116.15 E (In the Bering Sea):

“First part of this day had brisk breezes from southeast and foggy. Made sail at daylight steering north northeast, wind increasing. Middle and latter parts [of the day] thick and rainy, blowing heavy from northeast. Saw nothing but one humpback. At night took in sail. Had extra grub today, and the [crew] was allowed some gin, and some of them got a little corned in kicking up the Fourth of July.”

Wishing all our friends a safe and happy July 4th holiday. Don’t get too corned!

Sometime Between June 23 & June 30, 1898:

Damn The Torpedoes!

In 1891, the E. W. Bliss Company of Brooklyn, an early manufacturer of torpedoes, began testing their “fish” off Sag Harbor in Noyac Bay.

The goal of the test firings (there were no warheads attached) was to make sure the torpedoes ran straight and true. They would be fired towards a large net, and if they came close to hitting the center mark they would get a passing grade. Some of the torpedoes would veer off course in one direction or the other and miss the mark; these were hauled out of the net, adjusted, and re-tested until they worked as desired. When the Spanish American War broke out in April 1898, the testing became even more important.

By this time, Sag Harbor was “home base” for the Bliss Company testing program, with the torpedoes being launched from an old steamship the company had purchased named the Sarah Thorpe. Under command of Captain Thomas Corcoran, she had a crew of 13 that lived and worked on board.

While most of the testing was “run of the mill” stuff, one test firing during the last week of June 1898 was slightly more memorable. On this occasion, the torpedo ran “wild.” It missed the net completely, made a wide U-turn, and then headed straight for the Thorpe. Her engines stopped, she had no power to get out of the way. All the Captain and crew could do was watch in disbelief as this mechanical Moby Dick bore down on their ship.

Despite having no warhead, the torpedo did have speed and mass. If it hit the Thorpe squarely it would undoubtedly sink her. Luckily, the torpedo came in at an angle and only struck a glancing blow, allowing Captain Corcoran to avoid the ignominy of becoming the first sea captain in history to sink his own ship with his own torpedo.

One imagines an extra ration of rum or two may have been consumed by Captain and crew that night.

Bliss would continue to test fire torpedoes in Noyac Bay until the 1920s.

Jun 18, 1910

Sag Harbor Gets An “F”

In 1910, the State Prison Commission conducted inspections of facilities on Long Island, including the “lock up” in Sag Harbor. Their report (published in part in the Sag Harbor Corrector on June 18th ) found it to be clean and the interior freshly painted. The blankets were aired out once a week (a fact that seems to have been counted as a “plus”), and it was lighted by both electricity and gas. Meals for the prisoners were provided by a neighboring restaurant, the village allowing 35 cents per meal.

So much for the good news.

On the down side, the lock up had “unsanitary arrangements.” Despite the village having both water and sewage systems, there was no plumbing in the lock-up of any kind, the cells were not properly ventilated, and to top it off the entire building was thought to be a fire trap.

The inspection report ended in no uncertain terms: “This village is of sufficient size to provide a suitable place for the detention of prisoners. Until this is done, no prisoner should be locked up and left unwatched.”

The Village did make amends, albeit a bit slowly. A new jail was built and, um, ready for occupancy in 1916. Slightly confusingly, that new jail is now called “The Old Jail,” and is currently a museum, right next to the Municipal Building on Main Street, where you can go experience the vast improvements over the old lock up for yourself.

June 11, 1813

The British Are Coming…Again.

During the American Revolution, the British navy often stationed ships in Gardiner’s Bay, a sheltered area that allowed them to watch both Long Island Sound and the Connecticut coast. Sag Harbor provided a gathering point for food, fuel and fodder taken from eastern Long Island residents for use by British garrisons in New York City and Rhode Island. In May 1777, American Colonel Jonathan Meigs crossed the Sound from Connecticut and led a whaleboat raid on the British stationed at Sag Harbor with rousing success.

For the villagers, the War of 1812 must have been “déjà vu all over again.” In 1813 the British Navy once more took up position in Gardiner’s Bay, often demanding fresh meat and produce from the surrounding area with threats to attack if not supplied – or simply just landing and taking what they wanted.

An American militia garrison was stationed at Sag Harbor with trenchworks dug and cannon hoping to counter any British landing attempt.

On June 11 1813 that attempt came. Five barges of British sailors and Marines landed at about 2am, capturing three vessels, setting one of them on fire. The American response – both the Militia and citizens of Sag Harbor - was swift. The British were beaten back, with some accounts mentioning two dead. There were no losses on the American side.

For the second time in 35 years, British armed forces found themselves beaten at Sag Harbor.

June 8, 1870

The Iron Horse Arrives

The Long Island Railroad was incorporated in 1834, and be

gan operating trains between Brooklyn and Greenport in 1844. Although residents of the South Fork hoped and begged for train service for decades, it wasn’t until 1870 that tracks were finally extended out to Sag Harbor.

While trains had already been running between New York City and Sag Harbor for a few weeks, June 8th was chosen as the official “opening day.”

At 9:17 that morning, a special celebration train bedecked with flags and bunting pulled out of Brooklyn Station with about one hundred LIRR dignitaries and prominent New Yorkers on board, comprised of two elegant passenger cars and a smoking/dining car where, according to one newspaper item, the delegation “was provided an abundance of everything to sustain and cheer the inner man.”

Arriving at Bridgehampton, the party was taken by carriage to view the ocean, and then to a lunch at The Atlantic House, where the tables were “groaning with the weight of delicacies.” Re-boarding the train, the party made their way to Sag Harbor and was treated to an “elegant table with choice delicacies and wines” at the home of Mr. and Mrs. N. P. Howell. Afterwards, the made their way to the home of Mrs. Benjamin Huntting where “another spread with luxuries to tempt the palate” was offered.

With the afternoon growing late, the entire party boarded the train and headed back to New York City. Given the amount of food that seems to have consumed during the day, one imagines the trip back was somewhat slower - even a steam engine has its limits.

PICTURED: Postcard showing the Railroad Station c 1910 (it stood just east of the current post office)

June 1, 1898

Main Street Gets A Makeover

A load of “Peekskill gravel” arrived by schooner on this date, to be used to resurface Main Street. Prior to this the village streets were a mixture of sand, dirt, and irritation: Muddy in wet weather, dusty in dry weather, rutted and bumpy at all times. More loads of gravel would arrive over the next few months to complete the job.

However, the transformation was not without problems - two months after the gravel arrived a newspaper item reported that wagon drivers were doing “ruinous” damage by driving in the middle of the road, causing “a decided gully where the horses’ hoofs strike, as well as ruts where the wagons roll… the result is an uneven, chopped up roadbed that is already in bad shape and that by winter will be totally ruined.” It was suggested the village barricade the street center with barrels “to force vehicles to keep to one side.” So much for progress.

Main Street would be paved with concrete in 1922.

Drive safely, stay to the right, and enjoy your holiday weekend!

Pictured: Main Street in the year 1879 BG (Before Gravel)

May 26, 1817

Nero Fiddles...

On May 26th 1817 a small barn filled with hay - unfortunately located in the most populous part of the village - caught fire.

Fire was a constant danger in the early 1800s, as both homes and businesses of the time were full of ignition sources (fireplaces, candles, oil lamps) and firefighting technology was primitive at best - often nothing more than buckets of sand or water hurled towards the flames by men daring to get as close as they could.

Sag Harbor was possibly even more vulnerable than other villages; full of flammable casks of whale oil, barrels of pitch and tar (used to caulk ships and boats), miles of ropes, acres of sailcloth and thousands of barrel staves - all adding exponentially more fuel for a fire.

Once the flames escaped the barn there was little chance to stop the destruction. Within three hours some 20 of the best houses and shops in the village were in ashes. The speed at which the flames moved prevented people from moving their possessions to safety. Gale force winds hindered the firefighting efforts.

After the fire the villagers held a meeting, hoping to find “a means of relief for those suffering losses.” A committee was formed to solicit funds from near and far.

The village would rebuild and carry on, the profits from the growing whaling fleet no doubt helping recovery. But the villagers also took other measures: In 1819 a legislative act allowed the formation of a volunteer fire company in the village. The Otter Hose Company was formed that year, and still exists to this day.

Thank you to all our village firefighters past and present!

May 17, 1844

Send In The Clowns!

The earliest known circus show in America – it was a British circus on tour - occurred in the 1790s. George Washington is known to have attended one of the performances. In the first two decades of the 1800s, a number of American circus companies were formed. The first record of a circus visiting Sag Harbor was in 1838, and more would visit in the decades to come.

Here’s the advertisement for “The People’s Circus” that had their opening night in the village on May 17th 1844. They stayed in the village for about a week. Despite its proletarian name, it was actually run by a group known as The Zoological Institute, a syndicate that owned all the travelling circuses in the US. It was not the grandest of spectacles, with just a few acts, but it was no doubt an absolute thrill for all the villagers.

Eventually P. T. Barnum would revolutionize the circus business, first with his own travelling company in the 1870s, and later as part of “Barnum and Bailey” in the 1880s.

May 10, 1791

Reading Is Fundamental!

(First issue of Frothingham’s Long Island Herald)

Printer David Frothingham was just 25 years old when he moved to Sag Harbor, enticed in no small part by the exertions of several notable inhabitants - Customs Collector Henry P. Dering amongst them - to ensure his success. By the time he arrived, Dering and the others had secured about 350 subscribers for a new newspaper. The first issue of Frothingham's Long Island Herald came out on May 10, 1791. It was the first newspaper printed on all of Long Island.

With a customs house, newspaper and post office all established between 1789 and 1794, Sag Harbor was on its way to becoming the most important village on the east end.

Filled with local and foreign news, essays and a “poetry corner,” the paper came out weekly for seven years, ending its run in December 1798.

April 15th, 1861

Extra! Extra! Read All About It!